Most organizations do not wake up one morning and decide to become complex. Complexity accumulates quietly – one approval added after a failure, one layer added to manage growth, one exception created to serve a specific customer group, one workaround introduced to compensate for system limitations. Over years, these small additions solidify into a structural architecture that becomes difficult to navigate and expensive to maintain.

When leaders eventually notice complexity, it is not because someone complains about structure. It is because performance slows. Customers feel inconsistency. Decisions take longer. Innovation becomes incremental. Leadership bandwidth gets consumed by coordination rather than strategic thinking. These symptoms indicate a deeper issue: the organization’s operating system is no longer aligned with the pace and priorities of the environment in which it competes.

An organizational complexity study provides a disciplined way to understand how the architecture of work has evolved, where friction originates, and how simplification can restore speed and clarity. Unlike restructuring – which changes reporting lines but not underlying behaviors – an effective complexity study reveals the forces that shape how work truly moves inside the enterprise.

Context – Why this matters

Organizations today face a paradox. They have invested heavily in digital tools, analytics platforms, and cross-functional coordination mechanisms, expecting these capabilities to make decision-making faster and operations more adaptive. Yet many find that their internal systems slow them down rather than enable them.

The reason is structural: modern organizations have grown in ways that outpace their design. Digital channels multiply workflows; regulatory environments introduce layers of review; global footprints require intricate coordination; and legacy product portfolios add variation into planning, service, and supply chain processes.

McKinsey’s global research has long indicated that as organizations grow, the managerial load – meetings, escalations, reviews – tends to grow faster than the underlying business. This creates a form of internal debt: a backlog of decisions, unclear ownership, and duplicated effort that compounds over time.

McKinsey’s global research has long indicated that as organizations grow, the managerial load – meetings, escalations, reviews – tends to grow faster than the underlying business. This creates a form of internal debt: a backlog of decisions, unclear ownership, and duplicated effort that compounds over time.

Simplification becomes essential not for cost reduction but for strategic responsiveness. Organizations that remove friction can interpret market signals faster, allocate resources with more conviction, and execute with far greater consistency. In environments where agility is a differentiator, complexity becomes the tax that erodes competitiveness.

What Organizational complexity really looks like

Complexity is not merely the number of people or products. It’s an emergent property of how the organization’s elements interact.

There are four dominant sources:

1. Structural Accretion

Layers deepen over time, often unintentionally. A regional head is added to manage expansion. A specialist role is introduced to close a capability gap. Soon the organization has multiple managerial layers between the customer and the decision-maker. Every layer adds latency and blurs accountability.

2. Workflow Fragmentation

Processes tend to stretch across teams that were never designed to work tightly together. A simple onboarding workflow might involve sales, credit, compliance, operations, and IT – each with different priorities, SLAs, and knowledge bases. Fragmentation increases variability and slows throughput.

3. Governance Overload

New risks or failures often prompt new committees, forums, and checkpoints. Over time, governance becomes heavier than the work it oversees. Leaders spend increasing time in reviews that revisit decisions rather than clarifying them.

4. Informal Systems

Shadow workflows emerge to compensate for gaps in formal design. These include undocumented routines, reliance on tribal knowledge, and work that moves through backchannels. Informal systems create unpredictability and undermine standardization.

A complexity study seeks not to eliminate complexity entirely but to understand which forms are productive and which are corrosive.

How to Conduct an Organizational Complexity Study

A well-executed complexity study unfolds in four stages. Each stage reveals a different dimension of the operating model.

Stage 1: Identify the Strategic Tension Points

Simplification must be anchored in strategic intent. Organizations need to articulate the behaviors and outcomes the operating model must enable. Is the priority speed? Reliability? Customer intimacy? Innovation? Zara, for instance, designed its operating architecture around fast response. Its model – short decision chains, collocated functions, rapid feedback loops – was not built for efficiency alone but for strategic differentiation in a fashion industry where lead time shapes competitive advantage.

Zara, for instance, designed its operating architecture around fast response. Its model – short decision chains, collocated functions, rapid feedback loops – was not built for efficiency alone but for strategic differentiation in a fashion industry where lead time shapes competitive advantage.

Understanding strategic tension points helps determine what kind of complexity is harming performance and what complexity is necessary to compete.

Stage 2: Map Structural Layers and Horizontal Interfaces

This step clarifies the number of layers, managerial spans, and cross-functional dependencies. Many organizations underestimate their structural depth. A study at IBM during its ![]() business-unit consolidation revealed that overlapping roles and ambiguous P&L ownership created decision ambiguity that slowed transformation efforts.

business-unit consolidation revealed that overlapping roles and ambiguous P&L ownership created decision ambiguity that slowed transformation efforts.

A structural map exposes where decisions travel unnecessarily long distances and where role clarity is diluted. It also reveals hotspots – functions with many inward or outward interfaces – that often signal coordination overload.

Stage 3: Diagnose Workflow Friction

The most powerful insight often emerges not from structure but from observing how work moves. Mapping an end-to-end process uncovers hand-offs, queues, exceptions, and rework loops that are invisible in organizational charts.

Unilever’s multi-year effort to streamline supply chain and category operations revealed that many processes contained nested decision loops – small exceptions that triggered large review cycles. Simplifying these workflows, supported by improved data visibility, reduced operational variability and improved service levels across several categories.

Unilever’s multi-year effort to streamline supply chain and category operations revealed that many processes contained nested decision loops – small exceptions that triggered large review cycles. Simplifying these workflows, supported by improved data visibility, reduced operational variability and improved service levels across several categories.

Workflow diagnostics quantify where complexity impacts customers directly – missed timelines, inconsistent quality, unpredictable delivery – and where internal resources are consumed managing variation that should not exist.

Stage 4: Examine Governance and Decision Architecture

Complexity shows up most clearly in decision patterns. Which decisions escalate? Which get revisited? Which require multiple rounds of alignment? Which consume disproportionate leadership time?

General Electric’s recent separation into independent business entities was not simply a portfolio decision. It reflected an insight that governance was spread across businesses with fundamentally different economic models. Simplification of governance – not only structure – was essential to restoring focus and accountability.

General Electric’s recent separation into independent business entities was not simply a portfolio decision. It reflected an insight that governance was spread across businesses with fundamentally different economic models. Simplification of governance – not only structure – was essential to restoring focus and accountability.

Decision architecture reveals whether the organization is designed for responsiveness or caution. A complexity study helps determine which decisions should move closer to the frontline and which require clearer thresholds.

What Simplification Actually Means

Simplification is often misunderstood as cost-cutting or delayering. In reality, simplification is a redesign effort – aligning structure, workflows, governance, and culture so the organization can act with clarity.

Three lessons emerge from companies that have simplified deliberately:

Simplification begins with eliminating unnecessary variation

P&G’s portfolio rationalization in the mid-2010s was a simplification effort disguised as a business strategy shift. By focusing the company on core categories, P&G reduced variation across manufacturing, planning, and marketing systems, enabling sharper execution.

P&G’s portfolio rationalization in the mid-2010s was a simplification effort disguised as a business strategy shift. By focusing the company on core categories, P&G reduced variation across manufacturing, planning, and marketing systems, enabling sharper execution.

Simplification strengthens – not weakens – accountability

Unilever’s restructuring into Business Groups clarified P&L ownership and reduced the complexity of its previous matrix model. The intent was not cost reduction but coherence: fewer debates, clearer priorities, faster cycle times.

Unilever’s restructuring into Business Groups clarified P&L ownership and reduced the complexity of its previous matrix model. The intent was not cost reduction but coherence: fewer debates, clearer priorities, faster cycle times.

Simplification improves talent effectiveness

![]() Zara and Inditex show that when workflows are clear and decisions move quickly, creative and commercial talent can operate at full capacity. Simplification frees talent from coordination traps.

Zara and Inditex show that when workflows are clear and decisions move quickly, creative and commercial talent can operate at full capacity. Simplification frees talent from coordination traps.

The essence of simplification is not subtraction for its own sake; it is purposeful alignment of how work gets done.

Leadership Lens: What CXOs Must Rethink

A complexity study often reveals that the root cause of complexity is not flawed structure but leadership behaviors. Three shifts distinguish organizations that simplify effectively:

Leaders must value clarity over optionality – When leaders hesitate to make trade-offs, complexity grows. Clear priorities reduce the need for additional governance.

Leaders must examine decision velocity, not just decision outcomes – Organizations that move slowly are often not slower because decisions are difficult but because the architecture for making them is cumbersome.

Leaders must question whether the organization fits its current ambition – Structure is often a relic of past strategy. Simplification begins with aligning architecture to the future, not preserving it for the past.

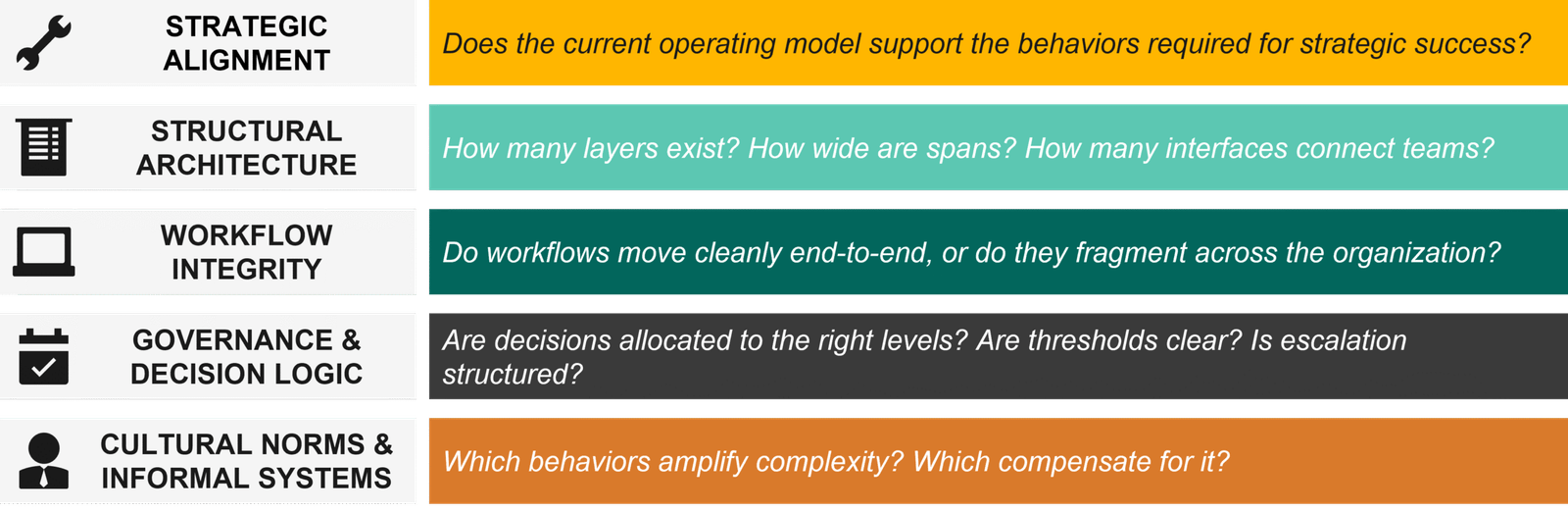

Strategic Framework: The Organizational Complexity Model

A useful way to conceptualize complexity is through a five-layer model. A complexity study traces how these layers interact to create friction, and simplification realigns them.

Implications for Mid-to-Large Corporations

Organizations with broad customer segments, multi-region operations, or diversified portfolios face unavoidable complexity. But unmanaged complexity erodes performance. For such corporations:

- Simplification improves customer experience by reducing inconsistency.

- Decision speed increases when governance becomes focused.

- Digital transformation accelerates when workflows are coherent.

- Talent becomes more productive when coordination burden drops.

- Leadership regains capacity for strategic work rather than firefighting.

In a world of ambiguity, simplification becomes a source of resilience.

Conclusion

Every organization accumulates complexity as it grows, but only a few manage it deliberately. A complexity study allows leaders to understand the architecture beneath their organization – the layers, workflows, decisions, and cultural patterns that determine how work moves. Simplification is not about making the organization smaller; it is about making it sharper, faster, and more aligned with strategic intent.

Organizations that simplify well tend to outperform – not because they have more talent or technology, but because they have removed the friction that slows both. In a decade where speed matters as much as scale, simplification may be one of the most underappreciated strategic capabilities.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

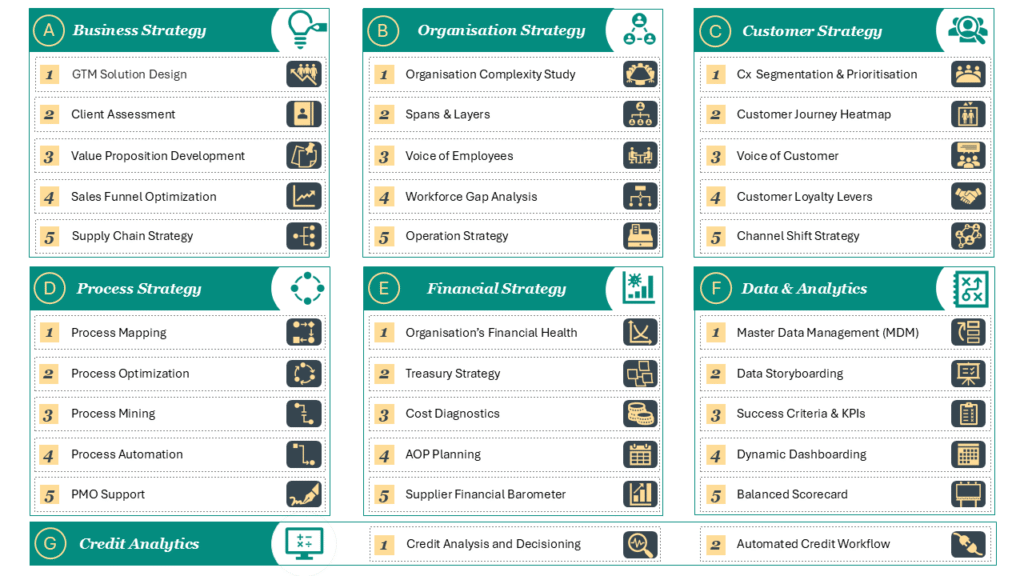

About Strategy Studio

At Strategy Studio, we help CXOs to solve complex business problems – from growth strategy and customer experience to financial transformation, process optimisation, and credit analytics. Our work blends rigorous analysis, practical execution, and deep functional expertise. To exlpore, schedule a free 30 minutes exploratory discussion HERE.

Other Articles

How to Assess Your Organization’s Financial Health for Strategic Growth

Why financial health has become a strategic constraint, not a reporting exercise Most organizations believe they understand their financial health

Cost Diagnostics: Identifying and Reducing Hidden Costs

Cost has returned to the centre of boardroom conversations, but not for the reasons many leaders assume. This is

Designing the Liquid Enterprise – Creating Organizations That Can Reconfigure Themselves in Real Time

For years, executives have described their organizations as “agile,” “adaptive,” or “responsive.” Yet in moments of disruption, many discover