For years, executives have described their organizations as “agile,” “adaptive,” or “responsive.” Yet in moments of disruption, many discover that their enterprises behave less like fluid systems and more like rigid machines. Decisions escalate slowly, resources remain locked in outdated priorities, and structures optimized for yesterday’s strategy resist today’s reality. The uncomfortable truth is this: most organizations are not designed to change shape while operating. They can transform, but only episodically. They can reorganize, but only after performance breaks. They can adapt, but only with significant friction. The idea of the liquid enterprise challenges this limitation. It is not about speed alone, nor about decentralization for its own sake. It is about designing organizations that can reconfigure priorities, resources, and decision authority continuously, without destabilizing the system.

This is not a cultural aspiration. It is an architectural problem.

Why Organizational Rigidity Has Become a Strategic Risk

The pressure for organizational fluidity is not driven by ideology. It is driven by structural shifts in how value is created. Markets now move faster than planning cycles. Customer expectations shift within quarters, not years. Capital-intensive bets are made under greater uncertainty. Competitive advantage increasingly depends on how quickly an organization can redirect attention and resources, not just on having the right strategy.

Yet most enterprises are still built around fixed assumptions:

- stable product portfolios

- predictable demand patterns

- clear functional boundaries

- centralized decision hierarchies

These assumptions no longer hold. What replaces them is not chaos, but conditional stability: the ability to remain coherent while changing configuration. Organizations that lack this capability pay a hidden tax. Strategy becomes a lagging activity. Execution trails intent. Leadership time is consumed by coordination rather than choice.

The question is no longer whether organizations need to be flexible.

The question is whether flexibility is designed into the system or improvised under stress.

The Myth of Agility and the Reality of Reconfiguration

Much of the language around agility obscures a deeper issue. Teams are often told to “move faster” without changing the structures that constrain them. The result is local speed and global drag. True liquidity is not about individuals working harder or teams operating autonomously in pockets. It is about the organization’s ability to reallocate four things in real time:

- attention

- resources

- decision rights

- execution capacity

Most organizations struggle not because they lack talent, but because these four elements are tightly coupled to static structures. Consider how capital is allocated. Annual budgets hard-code priorities months in advance. Even when leaders recognize a shift, redeploying capital mid-cycle is politically and operationally difficult. The same is true for talent, governance, and operating capacity.

A liquid enterprise breaks this coupling. It allows resources to follow reality, not plans.

How Some Organizations Are Quietly Becoming Liquid

The most instructive examples of organizational liquidity are rarely framed as such. They emerge in companies that were forced to rethink rigidity due to scale, complexity, or volatility.

Inditex, the parent company of Zara, is often described as fast-fashion excellence. But its deeper capability is organizational reconfiguration. Design, sourcing, production, and distribution operate on compressed feedback loops that allow priorities to shift weekly. Decision authority moves closer to real-time demand signals, without eroding overall coherence.

Inditex, the parent company of Zara, is often described as fast-fashion excellence. But its deeper capability is organizational reconfiguration. Design, sourcing, production, and distribution operate on compressed feedback loops that allow priorities to shift weekly. Decision authority moves closer to real-time demand signals, without eroding overall coherence.

Haier took a more radical path. Its microenterprise model dissolved traditional hierarchies, turning the organization into a network of small, accountable units that can form, dissolve, and recombine based on opportunity. This is not decentralization as ideology; it is structural modularity applied to management.

Haier took a more radical path. Its microenterprise model dissolved traditional hierarchies, turning the organization into a network of small, accountable units that can form, dissolve, and recombine based on opportunity. This is not decentralization as ideology; it is structural modularity applied to management.

Spotify’s well-known squad model is frequently misunderstood as a cultural experiment. In practice, it is a mechanism to allow product, engineering, and business capabilities to recombine rapidly as strategic focus shifts. The value lies less in autonomy and more in recombinability.

Spotify’s well-known squad model is frequently misunderstood as a cultural experiment. In practice, it is a mechanism to allow product, engineering, and business capabilities to recombine rapidly as strategic focus shifts. The value lies less in autonomy and more in recombinability.

What these organizations share is not a specific structure, but a common design principle: the unit of change is smaller than the enterprise.

The Core Tension Leaders Must Resolve

Liquidity introduces a fundamental tension that many leaders underestimate. On one side is coherence: alignment, consistency, risk control, brand integrity. On the other side is adaptability: speed, experimentation, local decision-making, reconfiguration. Most organizations oscillate between these poles. In stable times, they centralize for efficiency. In crises, they decentralize to survive. Neither state is sustainable on its own.

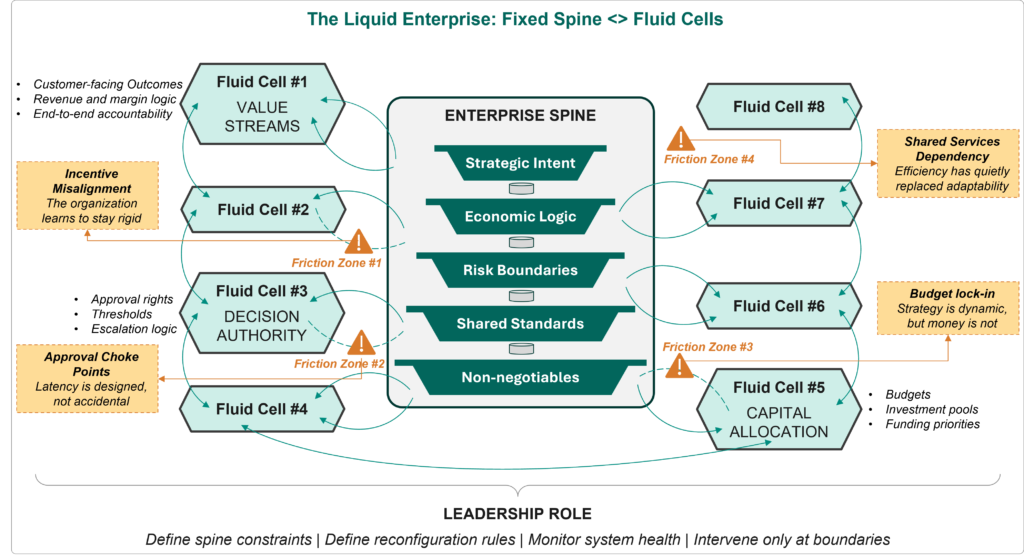

The liquid enterprise resolves this tension not through compromise, but through design separation.

- Coherence is enforced through shared principles, standards, and interfaces.

- Adaptability is enabled through modular structures and dynamic allocation mechanisms.

This separation allows organizations to change shape without losing identity. Leaders who fail to recognize this tension often default to extremes: either rigid control that stifles response, or uncontrolled autonomy that fragments the enterprise.

Where Organizations Actually Get Stuck

Most attempts to build more adaptive organizations fail in predictable ways.

First, leaders focus on structure rather than flow. Reorgs change reporting lines but leave decision pathways untouched. Work still queues in the same places.

Second, organizations confuse local empowerment with system-level flexibility. Teams may move faster, but dependencies remain unresolved, creating new bottlenecks elsewhere.

Third, governance lags design. Even when teams are reconfigured, approval rights, funding models, and performance metrics remain static. The system pulls the organization back into rigidity.

These failures reveal an important insight: liquidity is not a feature you add; it is a property that emerges from consistent design choices.

Where Liquidity Actually Fails (Mechanics, Not Intent)

Most organizations do not fail at reconfiguration because teams resist change. They fail because the mechanics of the enterprise actively prevent movement.

Three failure points appear repeatedly.

First, capital is structurally immobilized. Annual budgeting cycles lock resources into yesterday’s priorities. Even when leadership recognises a shift, redeploying funds mid-cycle requires exceptions, escalations, and political negotiation. Liquidity fails not because leaders lack conviction, but because capital has been administratively frozen.

Second, decision latency compounds silently. Approval thresholds designed for stability become choke points under volatility. Decisions that should take days stretch into weeks as they move across functions whose incentives are misaligned. By the time approval arrives, the underlying signal has often changed.

Third, performance management reinforces rigidity. Targets, KPIs, and incentives are typically calibrated to stable operating assumptions. Teams that adapt early often get penalised for deviating from plan, while teams that stick rigidly to outdated priorities appear compliant. Over time, the organization learns the wrong lesson: do not reconfigure unless explicitly told to do so.

These mechanics explain why many enterprises talk about agility while behaving rigidly. Liquidity fails not at the level of culture, but at the level of capital, authority, and incentives.

A Different Way to Think About the Liquid Enterprise

Rather than another framework of layers or capabilities, it is more useful to think of liquidity in terms of organizational physics.

A liquid enterprise exhibits four characteristics:

It reduces friction at points of change – Transitions between priorities, teams, and resource pools are designed to be smooth, not negotiated ad hoc.

It localizes instability – Change happens within bounded units, preventing disruption from cascading across the system.

It decouples decision speed from hierarchy – Authority moves dynamically based on context, not position.

It treats structure as provisional – Roles, teams, and configurations are expected to evolve, not persist indefinitely.

This is not about eliminating hierarchy or planning. It is about making the structure adjustable without breaking the system.

What CXOs Must Rethink

Designing a liquid enterprise requires leaders to unlearn several deeply held beliefs.

First, stability does not come from fixed structures. It comes from predictable rules about how change happens.

Second, control does not require centralization. In liquid organizations, control is exercised through standards, interfaces, and transparency, not constant approval.

Third, leadership is less about directing and more about designing the conditions under which reconfiguration is safe.

This shifts the CXO role fundamentally. Leaders become architects of adaptability rather than managers of scale.

There is a leadership behaviour that undermines liquidity and quietly kills liquidity more than any structural flaw: the instinct to intervene too late and too centrally. In many organizations, senior leaders allow local teams to operate autonomously until outcomes deteriorate. At that point, decision rights snap back to the centre, often accompanied by additional controls. The signal this sends is subtle but powerful: autonomy is conditional, and reconfiguration is tolerated only when sanctioned. Over time, teams stop adjusting early. They wait. Liquidity gives way to escalation dependency.

Designing a liquid enterprise requires leaders to intervene earlier and less visibly. The role of leadership is not to override decisions, but to design the conditions under which reconfiguration is safe, reversible, and rewarded. This is a difficult shift. It requires leaders to trust systems rather than instincts, and architecture rather than heroics.

Why Liquidity Matters Most for Large Enterprises

Small organizations are naturally liquid. Large enterprises are not.

Scale introduces inertia. Dependencies multiply. Risk tolerance declines. As a result, large organizations experience the greatest penalty when they cannot reconfigure quickly.

Liquidity allows large enterprises to behave like portfolios of smaller systems. Capital can move. Talent can be redeployed. Strategic bets can be resized without existential disruption. The alternative is slow decline masked by operational excellence.

A Forward Perspective

The next era of organizational design will not be defined by static models or universal best practices. It will be defined by how well organizations can change shape without losing coherence. The liquid enterprise is not chaotic. It is disciplined in a different way. It replaces rigidity with resilience, and predictability with adaptability. Organizations that master this will not simply respond to change. They will absorb it, redirect it, and use it to their advantage.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

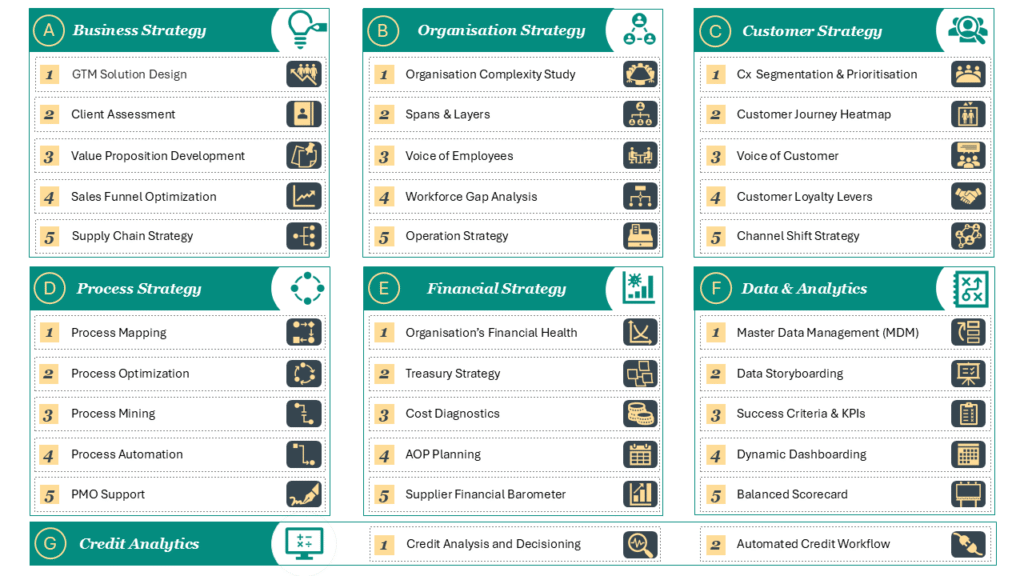

About Strategy Studio

At Strategy Studio, we help CXOs to solve complex business problems – from growth strategy and customer experience to financial transformation, process optimisation, and credit analytics. Our work blends rigorous analysis, practical execution, and deep functional expertise. To exlpore, schedule a free 30 minutes exploratory discussion HERE.

Other Articles

How to Assess Your Organization’s Financial Health for Strategic Growth

Why financial health has become a strategic constraint, not a reporting exercise Most organizations believe they understand their financial health

Cost Diagnostics: Identifying and Reducing Hidden Costs

Cost has returned to the centre of boardroom conversations, but not for the reasons many leaders assume. This is

AI-Ready Strategy Teams: The 2030 Tech Stack

Most strategy teams were built for a world that no longer exists. They were designed to synthesise reports, build